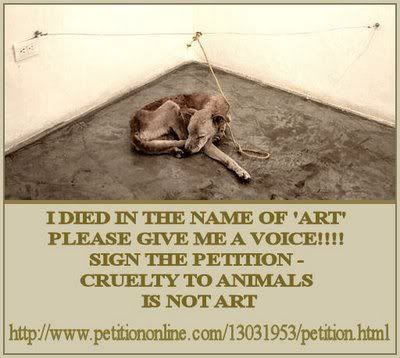

After reading Yate's and Plutarch's thoughts on Simonides, I realize that my definition of art was wrong. Art, in a snapshot sense (not dance or music), is images. It is an image so powerful it imprints itself into the mind so a viewer can never forget it. I wouldn't call Picasso's Guernica aesthetically pleasing (though it may be in a dynamic sense), but it punches you so hard in the stomach that it hurts. It is the perfect symbol to represent an idea--almost like a snapshot of it--A photograph of a waterfall, but instead of a physical thing, a mental ideal. Simonides, in his belief which Yates describes as 'the elusive relationship with other arts which run all through history of the art of memory are thus already present in the legendary source, in the stories about Simonides who saw poetry, painting and mnemonics in terms of intense visualization" (28), is then the rightful grandfather of mnemonics. Yates continues, saying "According to Cicero, the latter invention rested on Simonides' discovery of the superiority of the sense of sight over the other senses" (28). Art is an image that has been made to be remembered. A perfect mnemonic for something higher that cannot be described in words. In Guernica's case, of course it is the horror of war. When I picture Picasso's masterpiece, I see death, a horse neighing, its diseased tongue sticking out of its mouth, a dead body is thrown across the ground, a broken saber in his hand, an ox, the symbol of war, a mother with a dead infant, the chaos becomes one stark image. If that isn't a mental mnemonic for war, I don't know what is. And this is tied to sight like Cicero described, because sight is tied to so many other senses. Thus the image of the unmade bed becomes man's need to control his environment, the plastic surgery cube is the grasp for physical perfection at the expense of everything else, and the starving dog is death itself.

On page 30, Yates relates how in the Greek Ars memorativa treatise, the images for things (such as valour, cowardice, and metallurgy) were "deposited in memory with images of gods and men (Mars, Achilles, Vulcan, Epeus). Here we may perhaps see in an archaically simple form those human figures representing 'things' which eventually developed into images agentes" (30). In Tullius' description of the legal case, the Ram's testes can start to be made sense of, in that Mars is associated with the Ram. I think this is a valuable lesson because in the construction of memory palaces it would be helpful to have a culturally standardized image for each idea. In this class, it seems, we have been stumbling around in the dark to form a perfect image to represent something. But wouldn't it be helpful to already have a set-up picture to associate with these things? In Finance, we have forward and futures contracts. Both deal with an agreement to sell something at a set price sometime in the future; however, forward contracts are highly specialized and cannot be traded on the secondary markets like futures contracts can. Futures contracts are standardized and thus can be traded. Images can work in a similar fashion. The images we have been trying to construct are unique to each person, making the trading of ideas more difficult. My vision for the idea of 'love' may be extremely different than another person's, and thus the exchange becomes a strenuous process, so our modern world has made imagination even more important. Aristotle talked about imagination in his De anima, "The perceptions brought in by the five senses are first treated or worked upon by the faculty of imagination, and it is the images so formed which become the material of the intellectual faculty. Imagination is the intermediary between perception and thought" (32), and that the soul cannot think without forming images or 'a mental picture.' "Memory, he continues, belongs to the same part of the soul as the imagination" (33). Memories are 'paintings' in the mind, and thus art could also be seen as a visible representation of a memory that anyone can experience.

Metaphors could also be defined as mental pictures which relate one image to another, and "The metaphor," Yates writes, "used in all three of our Latin sources for the mnemonic, which compares the inner writing or stamping of the memory images on the places with writing on a waxed tablets is obviously suggested by the contemporary use of the waxed tablet for writing" (35). The mind is like a canvas that can be painted on. Plato described how these canvases or tablets already have images in them from before we were born--such as the example Yates gives of the idea of equality. In fact, everything in our heads may have already been there and "all knowledge and all learning are an attempt to recollect the realities, the collecting into a unity of the many perceptions of the senses through correspondences with realities" (37). Our recollections then must be echoes of the cosmos. Metrodorus of Scepsis used the Zodiac as his mental canvas. The stars above had pictures related to them, making the question of where the universe begins and the individual ends a pinpointed image. It also gave the memory a magical quality. Apollonius of Tyana, when he visited a Brahmin in India, focused on astronomy and memory, and esoterically, the Brahmin was said to have given him "seven rings, engraved with the names of the seven planets, which Apollonius used to wear, each on its own day of the week" (43). Cyrus from Persia was said to know the name of every soldier in his army. Lucius Scipio knew the name of every Roman citizen. Cineas knew all the senators, Mithridates of Pontus knew all 22 languages of the people in his lands, and Charmadas memorized every book in his library. Augustine believed that a divine presence was inside everyone's mind, giving each of us the power to recall past events and create worlds inside, just like God did in the beginning of time.

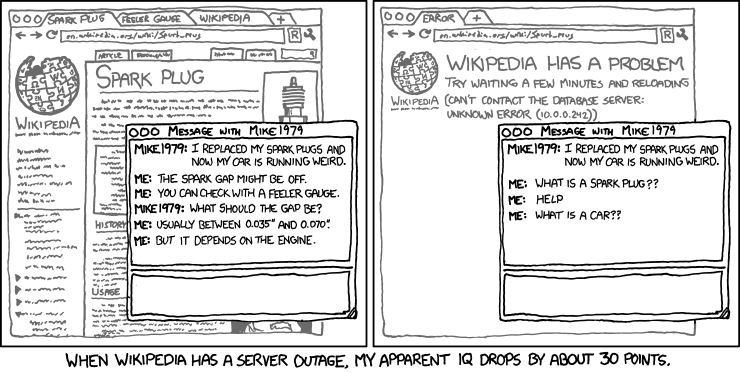

I want to end this with the myth Yates sites on page 38. When Thoth traveled to Egypt and gifts the written word, the king Thamus replied: "This invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are not part of themselves will discourage the use of their own memory within them. [...]" and they will appear wise "when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise" (38). I am reminded of this XKCD comic.

Is writing not an external memory? I think one of the most pure ideas of this would be the pensive in Harry Potter. The characters could literally take memories out of their head and put them in a bowl to be examined more deeply. You make mental images real--this is art, the transforming of memory to a physical representation. I always wondered if this was some meta-analysis J.K. Rowling was using to poke fun at the idea of writing in general. Since we mentioned Fahrenheit 451 class and I read that not too long ago, another thought was brought to mind which Bradbury used in that book. One character, I believe Faber, related that libraries were in fact the most important building in any community for if society fell to waste, it would be there people would go to rebuild it. Today that 'place' has been replaced by the internet. Thamus, who would seem to have spoken to us from the abyss of time, was a very prescient god. Google. Wikipedia. How To Sites. We don't need to remember anything anymore, and once technology has advanced far enough to place the world wide web directly into our craniums, I wonder what will happen to us? There will be socially augmented memories which can be influenced by anyone in the world. Jung's collective unconscious won't be a concept, it will be a fact. In another blog I would love to discuss Norton Juster's The Phantom Tollbooth and its play on words/numbers/and memories, or even delve deeper into a film which deals extensively with them like "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind", but here, alas, I will call it a day. Yates' book is truly a remarkable one that I will continue to throw myself against. And sorry for not engaging anyone's blog yet, that will be my next task.

No comments:

Post a Comment