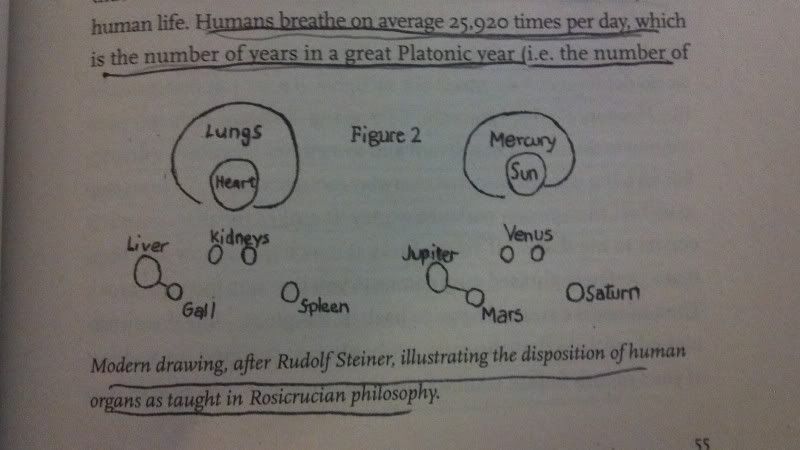

One could easily tie this in with Adam's naming of the animals in Eden. If anything that story is a history of consciousness, where the first man increasingly grew aware of the universe--first naming objects, then recognition of sex and nakedness, and then death and life. It's as if the world around him is materializing. The tree now exists because he has a name for it. So does the lion, the ox, woman, and even death. I suppose one could also take the entirety of myth as a mnemonic itself. Every story is didactic, powerful, and often recited during certain seasons or every three or five years. We can see this in Greece with the Greater Eleusinian mysteries. Often these tales remind the viewer of the planes of existence, of culture, of birth rites. Initiation enlightens the experiencer of the illusion of death, nature gods and goddesses remind of the cycles of the seasons and the folly of believing too much in the material universe, and Hero's journeys are an epic version of our lives told through metaphor. I could be wrong, but when I think of the ancients looking into the sky, I would like to believe they were seeing the memory of the universe, and this memory was echoed through everything, even their bodies. The organs in the body were tied to different celestial bodies and gods (Jung also believed the different archetypes were tied to the organs).

The thoughts in their minds were not their thoughts, but different deities/planets/organs waging war on each other, forming alliances, laughing. Olympus wasn't a real place, it existed in your mind. Jesus didn't actually rise up when he died, he went inward. Joseph Campbell says in "The Power of Myth,"

"If you read 'Jesus ascended to heaven' in terms of its metaphoric connotation, you see that he has gone inward--not into outer space but inward space, to the place from which all being comes, into the consciousness that is the source of all things, the kingdom of heaven within. The images are outward, but their reflection is inward. The point is that we should ascend with him by going inward. it is a metaphor of returning to the source, alpha and omega, of leaving the fixation of the body behind and going to the body's dynamic source."

In other words, these stories weren't to be taken as a historical texts but as images, as mnemonics, stories you could replay in your mind to remind you of certain things, usually pertaining to the meaning of life itself. This is why initiation during certain times of the year is so important. First it becomes a sacred act because that is how the 'universe' would remember them, but it also becomes a powerful memory for the individual. You now tie certain images to the setting you saw them, making the memories all the more powerful when you recall them later. It is interesting that so many myths deal with 'letting go of the material' because that is what causes the stress. It is also interesting that the 'memory palaces' we create is the same act God (or the gods) performed when He spoke the universe into existence--a grand act of imagination.

*The image was taken from "The Secret History of the World" by Mark Booth

No comments:

Post a Comment