Alison Lurie, in her article "Who is Peter Pan?", opines about writers being compared to gods: "they create men and women and children who seem to us to be real. But unlike gods, these writers do not control the lives of their most famous creations. As time passes, their tales are told and retold. Writers and dramatists and film-makers kidnap famous characters like Romeo and Juliet, Sherlocke Holmes, and Superman; they change the characters' ages and appearance, the progress and endings of their stories, and even their meanings" (Lurie). This is similar to what I presented in my last blog on Sean Kane's voices of the mythtellers.

Characters used in perpetuity by a host of different media and interpreters develop a life of their own. Did Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster foresee a modern Superman fighting Supergirl and the villains of Wildstorm inside the pages of the New 52? No, it would not only be improbable, but impossible from their point in history. Lurie brings up a good point--often when we perceive the author, we think of him or her as a god; however, the real question is who is controlling who? Many authors will tell you there comes a point when their characters start to possess them. They cease to be writing about them. Their creations are now writing through them. Grant Morrison wonders in Super Gods "if ficto-scientists of the future might finally locate this theological point where a story becomes sufficiently complex to begin its own form of calculation, and even to become in some way self-aware. Perhaps that had already happened" (119).

In Lurie's case, she grabs Peter Pan and uses his example to trace this collective phenomenon. "There have been scores," she says, "possibly hundreds of dramatizations and condensations, prequels and sequels and spinoffs. Some are interesting and even admirable, but there have been many cheap and even vulgar versions." As I was traversing to class today, following my invisible mind-map, I contemplated fictional characters' growth, except this time through the perspective of my own life. I have also gone through stages of development. I am constantly interpreted through the lens of the dominant culture around me. Sometimes I change, sometimes it changes. "What is a good life?" many ask. Some will answer that it is experiencing as much as possible, living through different moments, be they good or bad, and really taking in that particular scene.

A girl on Facebook posted today: "Life's goal is not to arrive at the grave in a well-preserved body, but rather to slide in sideways, totally worn out, drink in hand, yelling 'Holy Sh$t what a ride!' No fears, no regrets!" This is a similar idea--you need to LIVE life, not live life. I picture a gyrating wave, going up and down, up and down, up and down, relishing the happy moments but also the misery. A track through life is not the linear progression we are sold on by the American media. You do not collect 'happiness' as you make your way through school, graduating, getting a job and earning a living, marrying, and on and on. The only meaning in life is what you give it as you ascend up a particular incline, peak at the top in your victory, descend again and wallow in the trough. The truth is, there is no happily ever afters.

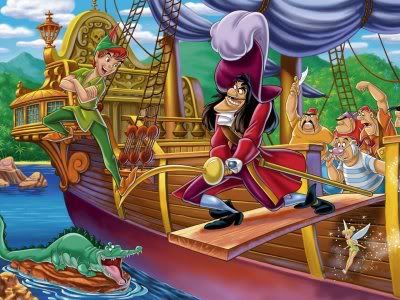

This drama is, of course, blown up by the images of our most famous icons. Like Lurie related, Peter Pan has aged. He has grown and changed with us. There is no example of a pop culture character becoming only more popular as history progresses. They either wane and disappear or become relevant again to a new generation.

We can also see this play out in celebrity worship, where a man or woman are used as the perfect representation of an idea.

Lurie details the iterations of "Peter Pan" over the years. How the story grew from a play, to a book, and into the modern era with Disney's film, Spielberg's "Hook", and the 2004 film about J.M. Barrie, "Finding Neverland". The Peter Pan story has also changed as the culture has. Tiger Lilly and the 'piccaninnies' have become less prominent as political correctness has taken hold. The animals skins have been changed to Halloween-esque costumes, and Peter Pan's selfishness has been downplayed. On top of his interpretations, the term 'Peter Pan syndrome' has become popular in psychology to define adult men who refuse to grow up, and Michael Jackson further popularized his Never-land Ranch, earning a sort of infamy after Martin Bashir's "Living with Michael Jackson".

All of these interpretations add a richness to Barrie's original creation. Just like at the end of your life, as you sit in a hospital bed and your great grand children ask you about your life, you can tell them about that time you climbed a mountain with your best friend, when you married your significant other, when you traveled to France, and most importantly your time spent learning about oral traditions. Peter Pan himself, with his inability to differentiate imagination from reality, his agelessness, his propensity for 'now' at the expense of remembering the past, and his violent tendencies, is almost the opposite of the constant death and regrowth I have described. The world is a very different place for children. Mermaids, pirates, noble savages, and dangerous animals outside your door can be real. They are just a flight, a cabinet, a tollbooth away. Peter Pan, as we have seen, can grow up, but the base image he represents has not yet changed.

No comments:

Post a Comment