[Getty Images from The Guardian]

There is a great magic in story-telling. It has the ability to transform a person, move him or her into new planes of consciousness. It can heal or destroy, make us laugh or weep, and sometimes within the same moment. Reality, as most of us in the West experience it, is quite boring. There is the constant drudgery of work or school, the endless cycles of waking in the morning and progressing through the tedium of the day. Because of modern mans’ separation from life-threatening experiences, there is a great need to find it in the pages of a book, the giant projector screen at a movie theater, or on the boob tube. Story appears to have always been a powerful escape for the human consciousness, however. It gives meaning to a terrifyingly pointless life. It allows us to be anything or anyone, which is impossible from a normal person’s typical existence. It makes us feel something, be it joy or repulsion. Literate culture is, of course, different. It puts an emphasis on the conclusion of a story, an authoritative version, as opposed to the oral tradition’s constantly morphing myths. It forces the teller to write in seclusion where the oral storyteller would be in front of an audience. It turns the collective mind inward where it had been outward. However, stories never went away. They are, in fact, a constant across all cultures and peoples. In this section, I will explore the magic of reading and story-telling: why in some respects there is still a great mystery to the process of story-crafting (like hypnosis) as neuroscientists and psychiatrists are learning much more about it. The magical tradition of reading, writing, and story-making stretches far back, and here I will make my stand on it.

New research has discovered that the human brain has a tough time differentiating between actually experiencing something and reading about it. According to the writer, Annie Paul in the New York Times’ article “Your Brain on Fiction”, “Words like ‘lavender’, ‘cinnamon’ and ‘soap’, for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells” (Paul). Though this may at first seem a failing of the body’s perceptions, it is actually a strength. It allows us to empathize with others through story and strive to make change in a world we may see as having injustices, bringing the group closer together. It also lets us communicate with beings from the collective unconscious—spirits that are bigger than one man or woman. They are representations of what society believes good or ill: a longed-for ideal like a knight, super hero, self-made businessman, or chaste woman. Celebrity icons like Jennifer Aniston, George Clooney, or Brad Pitt also become a ‘brand’ that can be sold. On the other end are evil images, like the thug (usually a minority), the ogre, the slut, or the greedy tycoon. Thus Bernie Madoff, Lindsay Lohan, and George Zimmerman can represent the collective unconscious’ negative ideas. These images are not actual people, living, breathing, with motivations, victories and transgressions, they are an absolute (though ones which can be appreciated more or less with the values of the surrounding culture). Words can give them life and release them to the ‘real’ world. I have never read Twilight, but I know who Bella, Edward, and Jacob are. Books, in their own way, are talismans! They draw down the gods and hold them between two covers.

In fact, in some esoteric circles during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, this was believed to be the case. A grimoire is a book which contains magical incantations and sigils, the most famous being the Ars Goetia, which was the first section of the larger work, The Lesser Key of Solomon the King. According to Wikipedia which cites Aleister Crowley’s translation: “The Ars Goetia ... [contains] descriptions of the seventy-two demons that King Solomon is said to have evoked and confined in a bronze vessel sealed by magic symbols, and that he obliged to work for him. The Ars Goetia assigns a rank and a title of nobility to each member of the infernal hierarchy, and gives the demons ‘signs they have to pay allegiance to’, or seals.” The writer of the grimoire is an unknown source from the 17th-century, but some of the material dates back to the 14th. The text claims that to summon spirits one must shout out the 72 names of the legions of hell. Practitioners of black magic often thought that the sigils themselves held the spirit inside, and that opening some books (written in human blood and made from vellum) would draw in invisible beings, making them exclaim: “What does the master desire to know?” ‘Grimoire’, interestingly, is an old French word for grammar. These spell books were magical litanies of sigils which, if spoken incorrectly, could cause great misfortune to fall on the magician who was performing the séance. Grammar was, of course, the utmost importance.

When a magician summoned spirits, the circle around him represented his domain, one which the invisible beings could not enter. It was thus an extension of his aura. In many secret organizations a rope was wrapped around the initiate’s waist, and during ancient times, this was actually the cord used during summoning. It would prevent an evil spirit from possessing the practitioner after the séance was over because if one syllable was said wrong, an “astral corpse” or imitating trickster spirit could be brought forth instead of the one desired. Chris Everard, a filmmaker, claims that the spirits usually appear solely in the Magus’ mind; however, if performed during an astrologically attuned time and spoken with exactly the right commands, you would be confronted by a spirit. These demons would appear in an alluring form as to seduce those around it—a beautiful man or woman, an old person, or a child. However, their true forms were often a mix between man and beast. This is a fear of the body, one which John Carpenter used to great effect in “The Thing”. For a typical person, the processes of the body are a mystery. There is a great fear in this, almost repulsion. Secret societies tied the organs and the planets together—thus, if the body became out of whack and started doing bizarre things like mixing animal and human it would be because the stars were going crazy. In “The Thing”, the creature which causes the grotesque transformations is literally an alien from a crashed spacecraft frozen in Antarctica. Body organs were also used to predict opportune times for battles. In Alexander’s age, bulls were killed before campaigns so soothsayers could read their innards to predict the outcomes of skirmishes. Ouija boards fall under this magical incantation tradition as well. Remember, these are just letters of the alphabet which the spirits use to communicate with a wayward soul. Could not books hold the same sort of terrifying power over the reader? Are you not permitting your mind to communicate with dangerous entities when you open the pages of a book? According to this tradition, the answer is yes. Certain words and music can excite the spirits’ emotions!

In fact, the author himself may be communicating with a higher authority if he writes from a subconscious state. Truly, if his words are clairvoyant enough, the spirit may go on to infect the masses around its original creator. Cultural figures like Superman or Batman have gone through many deviations over the years, and the same holds true for Harry Potter, who was originally created by just one author; however, after his ascension in pop culture, thousands, if not millions, have used their own voice to portray him, especially across different medium. Is it possible that man did not create these cultural icons? What if, instead, they were particular powerful gods who wanted to be known in the lower spheres? In The Secret History of the World, Mark Booth quotes Bob Dylan as saying that to change the age “‘you have to have power and dominion over the spirits. I had it once ... ‘ [Dylan] writes that such individuals are able to ‘... see into the heart of things, the truth of things—not metaphorically either—but really see, like seeing into metal and making it melt, see it for what it is with hard words and vicious insight’” (Booth 36). Booth says of this:

Note that he [Bob Dylan] emphasizes he is not talking metaphorically. He is talking directly and quite literally about a powerful, ancient wisdom, preserved in the secret societies, a wisdom in which the great artists, writers and thinkers who have forged our culture are steeped. At the heart of this wisdom is the belief that the deepest springs of our mental life are also the deepest springs of the physical world, because in the universe of the secret societies all chemistry is psycho-chemistry, and the ways in which the physical content of the universe responds to the human psyche are described by deeper and more powerful laws than the laws of material science (Booth 36)For a wider view, there have been eight films produced from J.K. Rowling’s books, artwork by thousands of artists, and maybe most importantly, the fan fiction littered across the web. Sites like fanfiction.net and MuggleNet allow users to log on and create their own stories with their favorite pop culture properties. There is a wide range of romances (be they between Hermione and Harry, or Harry and Hagrid), rewritings of established books, and further sequels. Harry is not the singular point of one woman’s imagination anymore; he is a lightning rod of our collective dreams and fears. He can be anything to anyone, and his books are not “delimited by the individual who writes alone and silently” (Wisdom of the Mythtellers, 188). Walter Ong’s ‘secondary orality’ lets the online community continue Harry’s adventures, though they may be apocryphal. We can compare this to the authoritative canon of the Bible, which was used to try and squash the writings of the Gnostics and other sects at the first Council of Nicaea in 325 BCE. The internet, in its own perverse way, is the voice of humanity—it is so alien, so intangible and logical, but it is also more human than any one person could be. It is our collective emotions, prejudices, logos, and mythos; it is everything great about us, but also everything wrong with us.

Grant Morrison, in his book about super heroes, Super Gods, says characters like Superman and Batman did not exist in a:

Close continua with beginnings, middles, and ends; the fictional ‘universe’ [of DC and Marvel] ran on certain repeating rules but could essentially change and develop beyond the intention of its creators. It was an evolving, learning, cybernetic system that could reproduce itself into the future using new generations of creators who would be attracted like worker bees to serve and renew the universe (Morrison 117)(His emphasis, not mine.) He goes onto to compare the characters to something like twelve-bar blues or a chord progression. Different writers could “play very different music. This meant interesting work could be done by writers and artists who knew what they were getting into and were happy to add their own little square to a vast patchwork quilt of stories that would outlast their lives” (Morrison 118). Myths, memes, and serials are similar to what one of my classmates described as ‘mind babies’ or ‘tulpas’ by Tibetan masters (‘thought-beings’). They can possess an age, live past their creators, and become something bigger than any one man or woman. The characters we create and adore are like the gods of old. They descend from the astral spheres and inhabit a person, speak through them, become them. The voices inside their head are not their own, but the gods’ divine thoughts. Sean Kane relates that myth-telling, like all communication, is a performance. We dance with each other without realizing it. In this way, we are God pretending to be human, a rabbit, or a bush because in the end, it is all an act.

Kane later compares old myths to a conch shell. They have been retold so many times that they spiral with the passage of time. Repeated stories develop a sort of richness because each voice adds a texture or echo. Right now we can see this in “The Hunger Games” film, where outspoken fans complained that something was left out or not done right. For a disgusting example, racist tweeters raged about the African American roles of Rue, Cinna, and Thresh not being what they imagined. This is a new story with clear echoes of past Dystopian tales like “Battle Royale” and “Mad Max”. However, as the years fall under the foot print of history and more movies, fan fiction, and art are created from Suzanne Collins’ works, the tale will only become richer, each new story adding baggage and depth.

Kane continues, describing how myths were told in hunter-gatherer cultures. “Beyond community,” he writes, “but not far beyond it, there is nature. For the oral societies that lived by hunting and fishing, nature was the very source of voices. It was like a huge, infinitely resonant drum. From it came the startling noises—the thunder and howling winds imitated in the sounding of rattles and drums of village celebration, noises meant to catch the spirit world” (Kane 190-91). The tales’ telling thus became a recreation of the music of nature—each drum beat mimicked a bird’s call or an elephant’s stomp, and the “energy of the singer invoke[d] energies in nature, which gather until the whole drum song hangs in a tumultuous and chancy kind of order, much like improvisational jazz” (Kane 191). Both Morrison and Kane used the metaphor of riffing to explain different speakers’ and writers’ interpretation of the same story. Kane calls this a polyphony, or “an echo in human expression of a world in which everything has intelligence, everything has personality, everything has a voice” (Kane 191). On the other hand is vulgar homophony, or human speech, cut off from the sounds of nature. It is the difference between the civilized sphere and natural one. One cuts up reality (‘consciousness-eaters’) the other is an untamed wholeness, taking in both good and evil un-biasedly. Agriculture, according to Kane, is when man started to feel he could own things and started competing with nature instead of being in harmony with it. In some aspects, stories are like a river. They change over the centuries, moving over new land, creating new streams, and if they last long enough, morph the landscape itself. However, during man’s time on earth, he has tried to control these paths of water, damming them and siphoning off water from the mother stream to irrigate his lands or fulfill the needs of his cities, or the perverse mirror, throwing his waste into them with disregard or overfishing from her waterways. Oral myth is the untamed river; written myth is the dammed one.

Myth, as I have tried to show, is everywhere. It is in the trees. In the rocks. In the rivers. In the sky. It is alive, almost as if the polyphonic voices of nature (the spirits) were coming together to craft a story. Myth is not static; it changes every time someone retells it. This is similar to how memory works, in that each time a person relives a memory, they mismember it subtly. It morphs to fit the arch they believe themselves to be on and because of this, a myth will die away if it is no longer relevant to the group of people which it is associated, just like we bury a memory which no longer fits in with our story. But others transform. The holiday of Easter is a pertinent example. It began as a pagan festival claims Heather McDougall in an article written for The Guardian. Jesus’ story was in the tradition of the dying-and-rising gods of the Neolithic peoples. “The general symbolic story of the death of the son (sun) on a cross (the constellation of the Southern Cross) and his rebirth, overcoming the powers of darkness,” McDougall writes, “was a well worn story in the ancient world. There were plenty of parallel, rival resurrected saviours too.” She mentions the Sumerian Inanna, who was also hung on a stake; the Egyptian god Horus, who was the resurrected Osiris; Mithras, who was celebrated on the Spring Equinox of sol invictus; and the Greek Dionysus, who died many times and came back again. Many of these gods were born on December 25th, which was near the Winter Equinox, an obviously pagan date, and the date when the Roman Saturnalia festival was held. It was easy for the early Church founders to gain converts if they placed Jesus’ birth near this date (there is nothing in the Bible proclaiming when the Son of God came into the world). Today, the celebration of Easter itself changes with “the phases of the moon”, and even today “many churches are offering ‘sunrise services’ at Easter – an obvious pagan solar celebration” (McDougall). Myths change to fit the audience’s collective perception of themselves. They are, in their own way, very much alive.

In contrast to characters being accepted as gods, Alison Lurie, in her article “Who is Peter Pan?” opines that instead of their works, writers are often compared to the higher authorities:

They create men and women and children who seem to us to be real. But unlike gods, these writers do not control the lives of their most famous creations. As time passes, their tales are told and retold. Writers and dramatists and film-makers kidnap famous characters like Romeo and Juliet, Sherlocke Holmes, and Superman; they change the characters’ ages and appearance, the progress and endings of their stories, and even their meanings (Lurie).Like I discussed above, characters used in perpetuity by a host of different media and interpreters develop a life of their own. Did Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster foresee a modern Superman fighting Supergirl and the villains of Wildstorm inside the pages of the New 52? No, it would not only be improbable, but impossible from their point in history. Lurie brings up a good point—often when we perceive the author, we think of him or her as a god; however, the real question is who is controlling who? Many authors will tell you there comes a point when their characters start to possess them. They cease to be writing about them. Their creations are now writing through them. Grant Morrison wonders in his aforementioned book “if ficto-scientists of the future might finally locate this theological point where a story becomes sufficiently complex to begin its own form of calculation, and even to become in some way self-aware. Perhaps that had already happened” (Morrison 119).

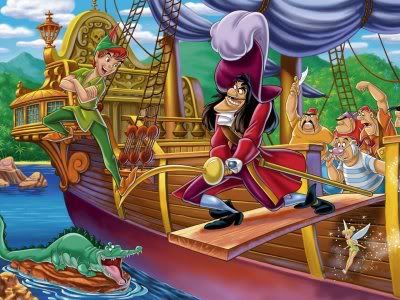

Lurie, for her part, details the iterations of “Peter Pan” over the years. How the story grew from a play, to a book, and into the modern era with Disney’s animated film, Spielberg’s “Hook”, and the 2004 film about J.M. Barrie, “Finding Neverland”. The Peter Pan story has also changed as the culture has. Tiger Lilly and the ‘piccaninnies’ have become less prominent as political correctness has taken hold. The animal skins have been changed to Halloween-esque costumes, and Peter Pan’s selfishness has been downplayed. On top of his interpretations, the term ‘Peter Pan syndrome’ has become popular in psychology to define adult men who refuse to grow up, and Michael Jackson further popularized his Never-land Ranch, earning a sort of infamy after Martin Bashir’s “Living with Michael Jackson”. All of these interpretations add richness to Barrie’s original creation. Just like at the end of your life, as you sit in a hospital bed and your great grandchildren ask you about your experience on Earth, you can tell them about that time you climbed a mountain with your best friend, when you married your significant other, when you traveled to France, and most importantly your time spent as an English major at Montana State University. Peter Pan himself, with his inability to differentiate imagination from reality, his agelessness, and his propensity for ‘now’ at the expense of remembering the past, is almost the opposite of the constant death and regrowth I have described. The world is a very different place for children. Mermaids, pirates, noble savages, and dangerous animals outside your door can be real. They are just a flight, a cabinet, a tollbooth away. Peter Pan, as we have seen, can grow up, but the base image he represents has not yet changed. He is a spirit possessing our modern age, one which still holds relevance in his current form.

It was Bob Dylan who talked of the spirits’ (stories, images, and characters) ability to mesmerize an age and the artist himself. It is almost as if the great gods are worming their way into the lower celestial spheres by using clumsy talismans. Booth writes of the gods, “If you believe that ideas are more real than objects, as the ancients did, collective hallucinations are, of course, much easier to accept than if you believe in a matter-before-mind universe—in which case they are almost impossible to explain. In this history gods and spirits control the material world and exercise power over it” (Booth 59). Where before humanity was in direct communication with the gods, now they are distant. The only way they can be contacted is through perverse means, and reading and writing are just a few of the ways. Inside a book, a person is free to commune with aspects of themselves that are hidden away or buried. Books, like any good talisman, have been burned for being evil. They can inspire great evil or great kindness. Later in the paper, I will discuss how books like the Torah and Bible have transformed our consciousness. Literate society has not killed humanity’s great mythos, it has only changed it. It has moved toward the Occult, to the Orient, to serials and cultural icons as I have shown, and finally to fantasy and outerspace. Myth and story, once recognized as a great societal linker, bringing together the young and the old and instructing on the proper ways of life, has died. It has moved into the hands of the few. Is it healthy that our stories and images are controlled by the wealthy? Capitalism has led to the commoditization of our cultural icons, and it has done this without the masses realizing what they have lost. However, the focus of this paper will not be on this, it will be on the importance of stories in our lives and how it controls our identities through the power of the left and right brain. The next section will cover the science of reading and story-telling. My hope is to show how transparent the differences between myth and science really are.

No comments:

Post a Comment